More than a Concert and a Speech

Moving Worship outside of a Performance in both Song and Sermon

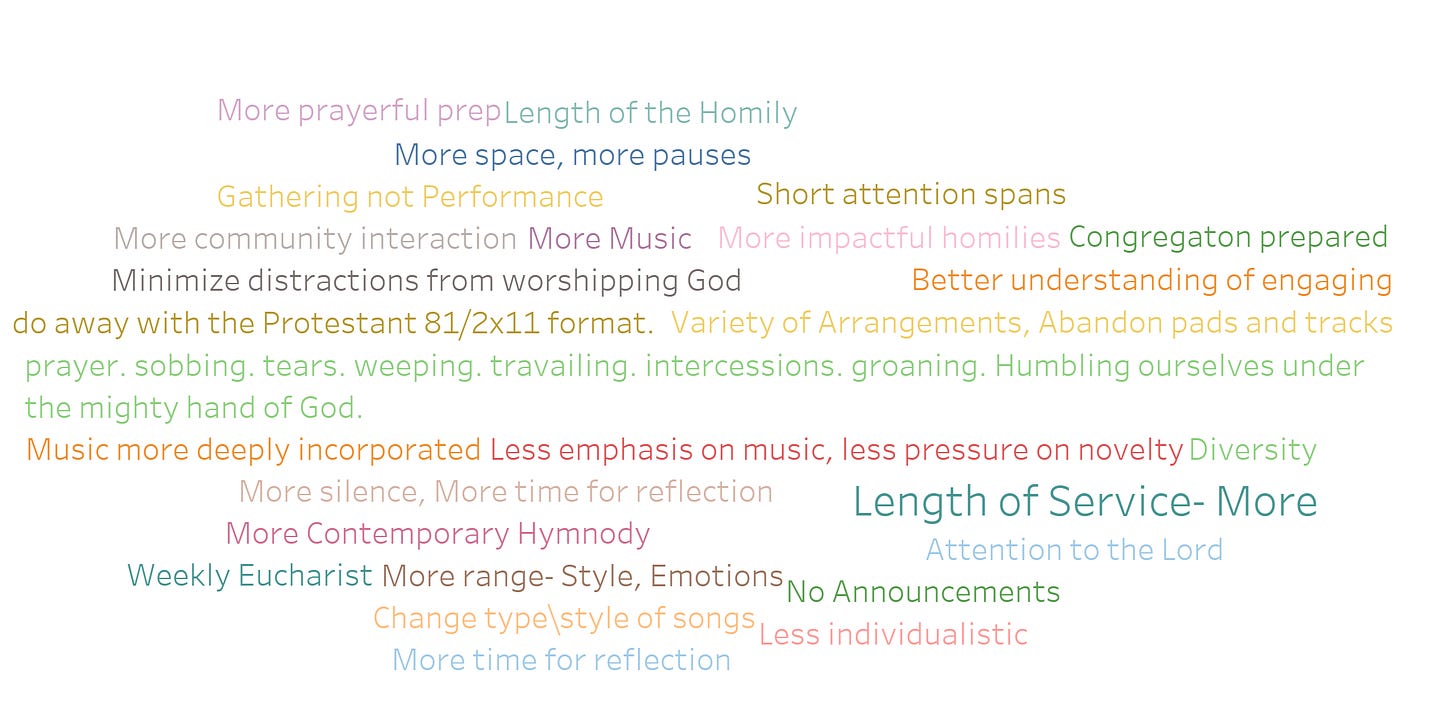

What is one thing you would change about worship services if you could? Why?

Worship leaders were asked about their desired changes in worship services. They expressed their hopes for both their local church and the wider Church, often connecting their local wishes to more encompassing desires. Their varied responses indicate their visions for the future of the Church, as what they felt needed to change in their services also needs to change overall. Several key ideas emerged and were echoed by other worship leaders from various denominations:

Community or Opening Concert?

A Non-Denominational worship leader responded that worship services need to “better emphasize the table, and the community. Not performance-oriented (a concert and a speech), but a gathering.” It can feel like, in some worship services, that the role of the congregation is to listen. The people in the sanctuary are there to be passive while the people on stage are there to be active. The service revolves around the stage, instead of being about the congregation engaging in relation with each other and with God. A Reformed Baptist worship leader adds to that sentiment when they say that “I would want them to feel even MORE like a gathering of a close-knit family where folks felt unashamed to participate to the fullest.” When you are at a concert, speech, political rally, you can feel like you are there with like-minded people who share something in common, but you can lose the sense of belonging to the community. One might have a temporary feeling of being seen or in community, but that moment fades when the event is over, and you realize that you do not really know the people around you nor do they know or understand who you are.

A Reformed worship leader noted that singing is not just preparation for the sermon but an opportunity to engage with God. In Reformed churches, which prioritize the Word, singing often becomes a secondary activity or an intellectual exercise that previews the sermon’s themes. It is either an extension of the sermon or a prelude to the main part of the service.

It is essential to recognize that within Reformed theology, the centrality of the Word manifests in both liturgical structure and ecclesiastical priorities. The homiletic focus inherently influences congregational activities, including musical worship. The act of singing, while perceived as ancillary, plays a crucial role in reinforcing theological concepts and facilitating spiritual reflection among congregants. As such, the Reformed tradition's emphasis on doctrinal precision and scriptural fidelity permeates all aspects of worship, underscoring the multifaceted purpose of congregational singing.

Another Reformed worship leader follows the same idea, writing that “I think we need more time for interaction in the pews with one another (not just singing) - because I believe worship is with God (vertical) and with His body (horizontal).” When church is a concert and a speech that requires no community, it becomes something one can engage with through their earbuds with no need to engage with others over. Churches might have times set aside for before or after the worship service for community-building, but by leaving time for social interaction outside of the service it may seem like community is not a priority in worship and can foster a mindset that “worship is only meaningful if the individual "gets something" out of it by the end,” as a different Reformed worship leader replied.

One can often judge worship by a two-fold rubric: Did I enjoy it, and Did my doctrines get affirmed? The previous posts have all highlighted the notion that worship is often seen as an activity to come out of feeling encouraged and enjoyed. St. Augustine, throughout his sermons, repeats the idea that sermons exist to edify and build up the congregation instead of challenge, provoke, or change the thinking or behavior of the person engaged in the service. Following Augustine’s understanding to an extreme, some churches have ended up only being concerned about the individual walking out feeling confirmed and encouraged.

Table or Stage?

Returning to the Non-Denominational worship leader’s response at the beginning of the last section, there is a desire for the Church to be centered more around the Lord’s Table and Eucharistic Meal than it currently is. The focus on the stage draws attention away from a sacramental moment that happens around the table. A worship leader from a Church of the Nazarene congregation writes that they “would love for us to receive Eucharist each week.” During the waning moments of a Church of the Nazarene services taking place outside of the survey area, I participated in one of the fastest Communions, where the pastor lifted the pre-packaged cracker and juice, read 1 Corinthians 11:23-25, opened the packaging, consumed the contents, and then dismissed the congregation as the congregants consumed theirs. The Communion part of the service took under 2 minutes. I do not think the pastor in the survey meant to add in moments like this to services. Nor do I think that either respondent meant that they should engage in the Eucharist in the way that Catholic and Anglican churches do, devoting a large swath of their service to the preparation, distribution, and eating of the elements.

Transitioning from a Baptist tradition with monthly Communion to an Anglican church with weekly Eucharist was surprising. Initially, I did not grasp its significance. However, years later, it now feels strange when a church does not have a weekly Eucharist. This practice has deepened my connection with others and God during services. As a chalice bearer, I witness diverse emotions in the eyes of congregants—joy, sorrow, or indifference—all coming together in a moment of shared presence with each other and God. I believe that the worship leaders who want to celebrate Communion or the Eucharist more, based on their other answers, want more moments of engagement between God and the congregation.

Reflection or Joyful Noise?

An Episcopal Priest simply wrote, “More space, more pauses” to answer the question posed. A Pentecostal leader kept it simple also, saying “More silence! I need space to contemplate.” A Wesleyan leader elaborates the point, “I think I said it earlier - more time for reflection. More effort put into what God has done, remind me of the good news again. Show us the love of God. Let us be still in His presence. Don't just race right to the easy emotions and obvious physical responses (hands raised).” Most of the worship orders from the churches surveyed move from song to song at the beginning of the service not leaving any moments for reflection upon what was sung or live in the emotions that were evoked from the song just sung. A Reformed worship leader writes, “I'd probably make” worship services “longer so we could sit in moments and engage more rather than rushing through. I think this would help form us for worshipping throughout the week.” In church, we can learn to flex our reflective muscles and start to live a more contemplative life.

Silence can enhance our senses, enabling us to hear and be heard, and it encourages us to seek similar quiet in other areas of life (Beeman 2005, 23–34). Though it may feel uncomfortable due to our lack of familiarity, silence can slow us down and make us more reflective. Practicing silence in the Church allows us to carry that calmness beyond its walls, helping us focus and connect by reducing the surrounding noise and letting our emotions surface naturally. Silence also allows us to sit for a moment and allow emotions to rise in us.

Why Are These Changes Not Made?

Why don’t leaders make the changes they desire? Some worship leaders want to remove announcements to maintain the service flow but recognize their importance for community updates. Others suggest shorter sermons to either reduce the service length or allow more time for singing. A few prefer longer services to include more content without cutting anything. So, what prevents these changes? There are a couple of easy answers.

The first reason is that the pastor, vestry, elders, deacons, or other leaders overseeing the worship leader do not support these changes. This could be due to adherence to a defined liturgy, such as The Book of Common Prayer or the Roman Missal, or because the existing order of service has been followed for many years and is now considered unalterable. The second reason is that the congregation may resist the changes. They might prefer extended periods of singing and personal devotional time with God and may not view the Eucharist as a significant aspect of their faith practice. Additionally, they may favor the dynamic nature of musical worship and feel uncomfortable with moments of silence during the service.

Worship leaders must consider others' preferences and may not always implement desired changes. For example, a church introduced and then removed corporate confession after negative feedback. Similarly, other changes may face resistance. However, worship leaders should strive to reshape worship for healthy emotional growth. Congregations and overseers should trust and allow them the space to make these adjustments for spiritual and emotional development.