Navigating Uncertainty with Art

Finding Inspiration and Clarity in the Unpredictable World of Creativity

I am currently examining Phillip Francis’ book, When Art Disrupts Religion, which explores the capacity of art to challenge the sense of certainty often associated with religious faith. The work suggests that engaging with art can encourage deeper faith by inviting individuals to confront questions and doubts. In analyzing Francis’ perspectives, I also consider the influence of emotional certainty and how artistic expression can dispel the notion that Christianity is solely characterized by joy.

Caravaggio painting of the Virgin Mary was rejected by the monks who commissioned it, as his painting portrayed Mary as a lifeless, everyday Roman woman, possibly modeled on a drowned courtesan. Its stark realism and lack of idealization were too much for its religious patrons. It was too real and not religious enough.

The Art Divide: Navigating Christian and Secular Creativity

At Bob Jones University, like a lot of conservative Christian institutions, the boundaries drawn around music and art were as stringent as those placed on sexuality—often, the two were considered inseparable threats. Outsider art was frequently spoken of as a Trojan Horse, smuggling in sinful practices, especially those of a sexual nature. Alumni recalled that entire genres of music were barred if they featured what was labeled as “sensual” electric guitars or “sexual” drumbeats. The language used to describe art from outside the Christian community—words like corruption, pollution, impurity—underscored a deep suspicion of anything that did not originate within tightly controlled boundaries. (80)

When I read that, I paused for a second thinking about putting those descriptors to the sounds of guitars or drums. How can that work? And then I thought about the greatest guitar solos I have ever heard, especially the slower ones by Pink Floyd’s David Glimour or Prince. Drumbeats being sexual still perplexed me. I can think about driving, aggressive, and intense drums. Or soft, smooth, crisp drums. But not sexual. It’s as if the conservative institution is trying to find a way to tie the sound that they do not like with an activity they think teens and children should avoid, while making it sound connected to sin.

This binary—insider versus outsider—are so fundamental to the individuals in these communities that, for many, even after leaving conservative church circles, it remained difficult to move beyond it. The world was habitually divided, and every attempt to think outside these categories required intentional effort and, often, personal struggle.

One story that stood out to Franics was the one of Joe, who as a child, was exposed to U2’s The Joshua Tree at his babysitter’s house. The experience was enthralling, but afterward, Joe grappled with guilt, unsure of the spiritual consequences of having listened to “secular” music. His story illuminates the complex emotional terrain navigated by many Christians when engaging with art from beyond the walls of their tradition. (85) The music was moving, but was it moving him towards all that was good and holy?

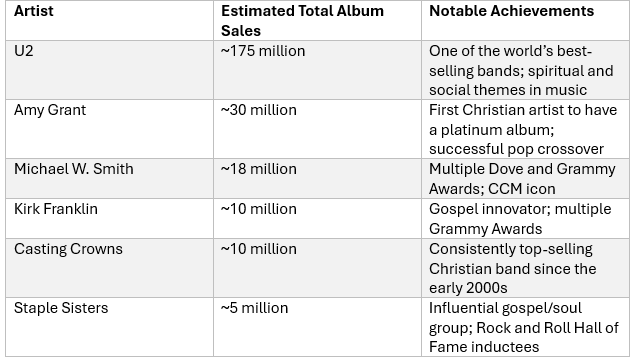

The irony is that album is probably one of the most perfect Christian albums of all time. Growing up, it was a dirty secret that U2’s album War was the best-selling Christian album of all time. U2 are probably the best-selling Christian band of all time. The Joshua Tree has rich spiritual and biblical imagery, but the problem is that U2 does not write worship or doctrinal music, and their lyrics often explore doubt, injustice, and longing—spiritual themes that resonate broadly but don’t always align with evangelical messaging. Bono and other members have openly criticized institutional religion, even while affirming personal Christian beliefs. This tension between faith and critique makes them spiritually provocative but not institutionally aligned. The fact that U2 explored, and continues to, explore the aspects of life which are out of bounds for some conservative Christians makes the band themselves out of bounds for Christians. The deeper irony is that the fact that U2 wrestled with these themes and used well-performed music to do so, it was easy for youth to listen to U2 and feel immersed in feelings that they were\are not allowed to have.

Yet, in these moments of aesthetic experience, something remarkable occurred. Individuals found themselves immersed in worlds that resisted neat categorization. Art challenged the insider-outsider binary, revealing complexities and particularities in both “outsiders” and “insiders” that could not be easily dismissed. The aesthetic encounter became a space where certainty gave way to a deeper appreciation for nuance and ambiguity. (89)

I remember being caught up in the poetics of The Smashing Pumpkins’ lyrics in a way that only Rich Mullins surpassed. Even if the words Billy Corgan wrote do not hold up, they explored the world in a way that was foreign but familiar to me. “Disarm” and the rest of Siamese Dream was musically and lyrically game-changing for me. I remember finding my world expanded when I discovered that their bands that heavier than Petra and Whiteheart. (Whiteheart tended to explore more of the emotionally taboo subjects in their later albums.)

Interestingly, the division of art along denominational lines was less pronounced than one might expect. Only in the most fundamentalist communities were certain groups, such as Catholics, systematically excluded. For the most part, the conversation focused on the broader distinction between what was considered Christian and what was not, rather than on sectarian differences. For some, the umbrella was quite large to be under, but not large enough to include all Christian artists. You still see that today. Think about the songs you listen to on the radio and sing in church. Do they all perfectly align with your denomination or church’s doctrines? The answer is probably not. And you probably do not think about that unless confronted by it.

As a practical theologian, I see these stories as invitations. They urge us to reconsider the boundaries we draw between ourselves and others, between sacred and secular, between purity and messiness. Art, whether Christian or not, offers us a chance to encounter God in the uncertainty, the complexity, and the beauty of human experience. Perhaps the real divide isn’t between artists, but between those willing to cross boundaries and those who remain behind their fences.

By keeping out U2, you are removing one of the best original lament songs from the lips of Christians who can use it to worship faithfully during their times of doubt and sadness. These words are sandwiched between the phrase, “But I still haven’t found what I’m looking for,” and show the doubt and devotion present in the song:

I believe in the kingdom come

Then all the colors will bleed into one

Bleed into one

But yes I’m still runningYou broke the bonds

And you loosed the chains

Carried the cross

Of my shame

Oh my shame

You know I believe it

There’s a clear confession of the Lordship of Christ in the singer’s life, while affirming Christ’s salvific work on the Cross. But it feels like it’s not enough sometimes. “Speaking with the tongue of angels” only lasts a bit.

Even though it’s on a different album, we have their song “Beautiful Day” as a great contrast. It is, as Bono (the lead singer) once explained, about a person who lost everything, but finds joy in what they still have. It’s about hope and perseverance while finding joy in simplicity. It’s also a song affirming the goodness of God’s creation while telling the story of redemption, as the words move from describing difficult circumstances to finding God’s grace.

To maintain intellectual certainty towards the propositions that the church wants people to ardently hold to create hard boundaries that often exclude works of art and media that would lead someone to naming or encountering doubt. As I continue to point out, even less strict denominations undertake that work by going as far as excluding readings from Scripture in their lectionaries.

The same hard boundaries are erected around art and media exist in the emotional realm. Laments, even those found in the Scriptures, are removed or re-tuned to turn into songs of praise by pulling out a verse and making it the focal point. We take Job 19:25, “I know that my redeemer lives,” out of the chapter so that we can have a beautiful Easter hymn. In doing such, we remove the harshness of the rest of the chapter and the emotional outpouring that adds nuance to the words. The words lose any sense of resignation and only become a joyful cry of praise, stripped of the context to the point most do not know the rest of the chapter.

Listening

I am struck by how deeply these boundaries shape not only our listening habits but also our very ways of relating to others. For many within evangelical communities, engagement with those outside their faith—especially through music—has been approached with a sense of mission. Interactions with non-Christians were often permitted only for the purpose of witnessing, and even then, these encounters were filtered through the lens of conversion. Even if it wasn’t phrased that way, it sometimes felt that the only reason you were friends with people from outside of the church was to bring them inside the church. Some churches were more overt about their witnessing, but growing up Baptist it felt like I had to try to bring people in, or I was wasting a friendship. Outsiders were frequently seen as projects, their stories redirected toward predetermined spiritual ends, rather than being genuinely heard as fellow travelers on the human journey. (90-91)

This posture of directing, rather than listening, is not merely a matter of evangelistic strategy; it is bound up in a larger emotional and spiritual divide. Psychoanalytic thinkers from Freud to Žižek have argued that it is our discomfort—sometimes even revulsion—with the desires of others that sustains these barriers. Yet, when we approach art and music, particularly from the so-called “secular” world, we are offered an opportunity to move beyond mere tolerance of the other. In the encounter with powerful, successful works of art, we might find that the very desires we once viewed as foreign are awakened within ourselves. The artist, in her vulnerability, communicates her hopes, longings, and the messy beauty of her humanity in ways that resonate with our deepest selves. (94) There is something to be said about putting ourselves in front of that which makes us uncomfortable. I am not saying that we necessarily need to transgress our morals, but sometimes we do if that moral boundary is wrongfully imposed by authorities trying to control us. What I am talking about is looking at and engaging in art that is sublime, art that pushes us a little bit while allowing us to stay in a safe place. It’s watching a horror movie or reading a book that tells a compelling story about human suffering. That can range from Ghostbusters to Angela’s Ashes to The Babadook. Ghostbusters engages with the dark side of the world from a humorous perspective, keeping us laughing. Angela’s Ashes tells a story of poverty and hardship while maintaining hope. The Babadook is a horror story about grief and mental health. All of these would not fit in a lot of conservative church’s list of approved media to engage with, but can help shape our understanding of the world, grow us emotionally, and strengthen our emotional wellbeing.

The art being compelling and connecting at the level of emotional connection “depends on context and reception.” (95) Experiencing art depends greatly on time and setting. Works that once seemed unremarkable, like Rembrandt’s “Prodigal Son” or Caravaggio’s “The Calling of Saint Matthew,” now resonate with deeper meaning for me. My perception of movies has also shifted based on mood and circumstance, such as finding Silence of the Lambs truly frightening during a thunderstorm. Preisner’s Requiem for my Friend became especially poignant after the loss of the friend who introduced it to me, and hearing its lacrimosa now always moves me to tears.

“Secular” media, then, is not just a source of potential danger or contamination; it can be a space where barriers are broken down on the level of emotional connection. Whether in a concert hall, a car ride, or a moment of private listening, we might find ourselves sharing common ground—and even common desires—with those we once considered “outsiders.” These moments reveal to us that the world is not so neatly divided, and that beauty itself is a form of welcome. As Francis writes, beauty calls out to us, declaring, “there is no fence between us.” (96)

To remain faithful is not to shut ourselves off from the complexity and richness of the world, but to trust that God meets us in the ambiguity, the longing, and the shared humanity that music—Christian and secular alike—can awaken. By listening, truly listening, we discover that our faith is not diminished, but expanded. The boundaries become more porous, and we are invited into a deeper, more generous encounter with both God and neighbor.

If you enjoyed this post, I would be so grateful if you considered supporting my work by buying me a coffee! I’ll probably save it all to buy scotch, but it sounds classier to say coffee.