What Emotions are Evoked during your Worship Services?

I asked the worship leaders in my study what emotions they feel during their services. I had them rank eight emotions: Praise, Adoration, Thanksgiving, Joy, Confession, Petition, Sadness, and Anger. You might think I am stretching the definition of emotion here, but I am trying to capture the vibe of these church worship services. That means there are more emotions at play than usual. I did not provide definitions because I wanted the worship leaders to use their own interpretations.

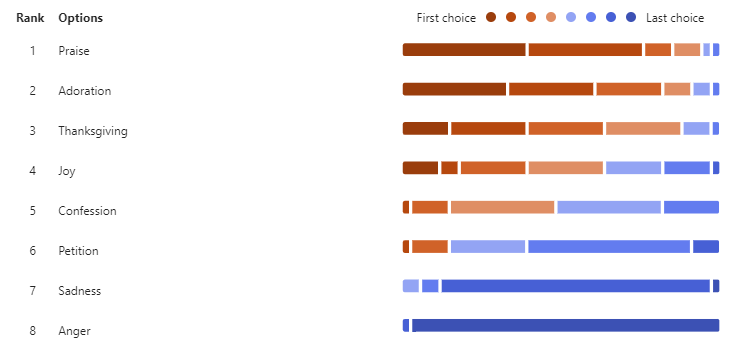

I thought that a few things would happen in the rankings. I believed that Praise and Adoration would dominate and that Sadness and Anger would be often ranked last. And that is exactly what happened.

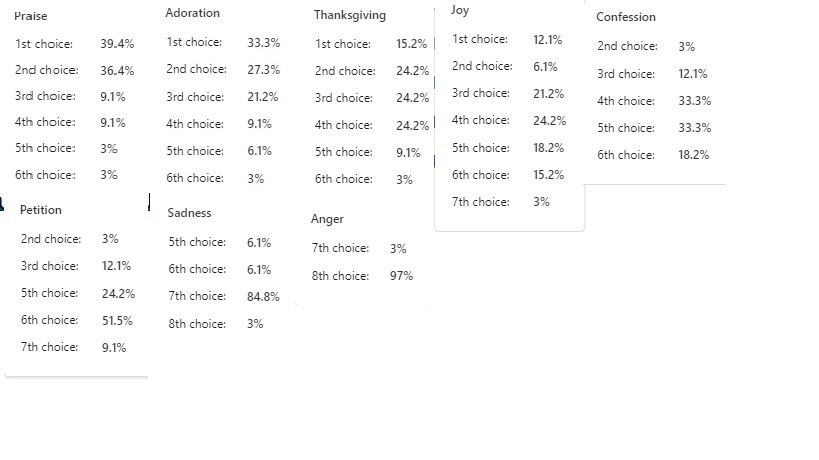

The results look like what I thought they would look like for the most part. Praise, Adoration, Thanksgiving, Joy, and Confession seem to be the dominate emotions in the worship services. Petition, Sadness, and Anger appear to always be in the bottom of the rankings. If we break those results down further, some interesting data appears.

The first interesting finding in the data is that there are only three choices that are above 50%, and all of those are in the 6th, 7th, and 8th place in the rankings. Petition as the sixth mood is at 51.5%, Sadness is 84.8% at the 7th choice, and Anger is 97% as the eight choice. That set of data tells us two things. The first is that there is no real dominant 1st-5th ranking of an emotion. I went into this, as I said above, thinking that Praise, Adoration, and Thanksgiving would be the dominant emotions. I also thought that Praise would be ranked 1st 51% and then the others would circle around that for the first ranking, and Adoration would be ranked 2nd around 51% of the time. I was impressed by the diversity of the rankings as it was unexpected.

The second surprising finding is that confession was ranked lower than expected. Considering worship services often center around sin and redemption, it seemed logical that Praise would be ranked first, as reflected in Psalm 95:1. I assumed that with a focus on Praise for salvation, confession would also be prominent due to its role in seeking absolution. However, confession remains a minor part of worship services. Even in the Anglican church, where The Book of Common Prayer places confession after the Call to Worship and before the Eucharist, it is ranked low. Similarly, Lutheran services place Confession after the Invocation, yet it still holds a lesser focus. On the same note, Petition is often ranked low as a priority, as it goes hand in hand with Confession.

Thirdly, as shown by the results separated by individual church response, there is no agreement of what mood or vibe should be dominate between churches inside of the same denomination. I am not surprised that the Non-Denominational churches have different emotional priorities as they only share loose connections with each other. I figured the churches with the most denominational ties to each other would follow the same emotional beats. For example, if we look at the three Episcopal churches who responded, we see these results:

Below is a searchable listing of the denominational affiliations of the individual churches and how they replied. You can see how differently the churches order their services around emotion.

What this All Means:

The Christian Church centers its worship on praising God for the redemptive work accomplished by Christ, expressing adoration for God's nature, and adopting an attitude of thanksgiving for salvation and divine intervention. However, it appears that the Church does not emphasize the reasons for needing Christ to act or intervene. Petitioning God for action and confessing sins occur less frequently than singing about sins being taken away or celebrating divine intervention. This ordering of emotions suggests that our joy may be incomplete due to a lack of confession and confession.

We see the exclusion of these emotions from our worship services because they are not in our hymnals, song lists, or prayer books. The theologian Lester Meyer, in his work “A Lack of Laments in the Church's Use of the Psalter,” shows how exclusionary the prayer books are. Meyer found the Lutheran book of worship excluded twenty Psalms from being used in worship which are either lament Psalms or have lament-like expressions in them. [1] Thirteen of these excluded Psalms are classified as individual laments by the Form-Critical method of labeling the Psalms, while seven of them are labeled as communal laments.[2] Meyer continues that the Lutheran book of prayer has sixty Psalms which are excluded from use in worship corporately, of which, forty-three of these sixty are “laments or lament-like.”[3] Meyer concludes that laments are underrepresented in the use of the Psalter in the Lutheran tradition in corporate worship.

Meyer found comparable results when he examined the Episcopalian book of common prayer. The Episcopalian book of common prayer excludes sixty-seven Psalms, of which twenty-nine are individual laments, eight are communal laments, and a further eleven are Psalms that have content that share aspects with lament.[4] Seventy-two percent of Psalms excluded from use in worship in the Episcopalian tradition are laments or have aspects in common with lament. According to Meyer, the pattern continues in the Roman Catholic book of prayer. Meyer found the Roman Catholic book of prayer book excluded seventy-eight Psalms, of which thirty-three are individual laments, eight are communal laments, and twelve others are lament-like.[5] Meyer finds that sixty-eight percent of the excluded Psalms are laments or close to lament. Again, we have an under-representation of Psalms of lament that the Church is using in worship. In the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, there are passages that are excluded because they are not suitable for public worship and liturgical use, like the majority of the lament and imprecatory Psalms, along with passages that seem less relevant to the themes of worship and prayer. The Church, in its guidelines for worship and liturgy, often follows that pattern. Somehow, passages of Scripture are not appropriate for use in worship, even if they were included in temple worship.

Meyer’s work brings us to the conclusion that multiple mainline Churches exclude the expression of lament in the private and corporate worship of their congregations. A cursory look at the lyrics of the yearly ranked top twenty-five worship songs used in Churches since 1986, according to Christian Copyright Licensing International shows that lament is not present in these songs and that they reflect what we have been calling redemptive sadness when they broach the topic of sadness and sorrow. We can move from these conclusions to the thought that, if the exclusion of expressions of lament in worship leads to a depreciative view of sadness, that the Church does not value sadness enough to include it in their expressions of worship. We can further claim that the singing of lament would grant explicit and implicit permission to express sadness in worship, both with the community and in the personal practice of worship.

Ending with a more personal note, when I published my paper on the lack of sad songs in the CCLI Top 25, one reviewer asked if I was suggesting that we sing imprecatory Psalms like Psalm 88 and I said that we should. They were taken aback by the suggestion that we should express anger towards people in our worship, even though there are multiple instances of people in the Scriptures taking their anger to God and expressing it directly either with God or towards people around them. Again, we need to bring our full emotional states to God and have the tools and opportunities for expressing them.

[1] Meyer, “A Lack of Laments in the Church's Use of the Psalter,” 69.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 70.

[4] Ibid., 71.

[5] Ibid.